If you weren’t here last week, here’s Part I

TL;DR:

If you’re working with an individual client who’s in a fight, or with a couple who are at loggerheads, consider the ways that structures of oppression like patriarchy and white supremacy might be the ultimate source of the conflict.

By talking about the ways structures provide the context for an “individual conflict,” the therapist can help the client develop empathy for both themselves and the other. Understanding structural violence not only facilitates our compassion for other people’s behavior; it can also open up new ways to overcome internalized oppression and work through a conflict.

Last week, we left Claire and me pondering her feelings of competition, alienation, and loneliness, both in her friendship with Emily, and in her friend group from childhood. She was watching the group split into factions, feeling helpless to stop it. She was defensive about her life choices and her resentment of her friends, and she was angry at herself for having these feelings in the first place.

But there was one feeling that left her particularly unsettled. “Why am I so envious of Emily?” she asked me, flopping back against the couch pillows in a huff. “I’m such a pain in the ass! Nothing is going to make me happy in my life—not my relationships, not my career, not my kids, if I ever even get to have kids, and god knows maybe I’ll hate that, too! Why would anyone want to be with me, anyway? I’m so difficult! I can’t imagine how it feels to date me.”

She looked at me out of the corner of her eyes, half-afraid I’d be nodding along with her self-assessment. We laughed together, and then ruefully returned to the subject at hand: what was she going to say to Emily? Would she have to fess up to these difficult feelings? Would Emily be disgusted by her, and walk away? Would it be better to apologize for being difficult, and hope everything would just get better in time?

“You know, I’ve been thinking about your fight with Emily,” I said. “If it’s alright with you, I’d like us to step out of this particular conflict and put it in a larger context. Earlier, I said I thought you and Emily were actually fighting about two versions of female ‘success.’ We noticed the women in your friend group seem to believe they have to choose between having a career and having a successful marriage, with kids. And part of your frustration right now is that you wonder if they’re right. You fear that because you’ve chosen to pursue grad school and a demanding career, you’ll end up alone.

“The question becomes: what were you and your friends taught, both by the dominant culture, and your families of origin, about what it means to be a successful woman? How did we get to this place, as a culture, where women feel this tension, and this scarcity of available time? Why are the choices women make watched so closely by other women, and why is there so much judgment about what they choose? We can find some of the answers when we look at history.”

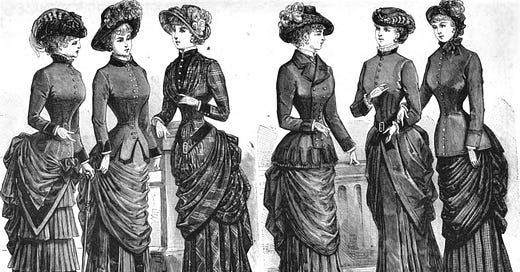

The division of the social order into a masculine world of competitive work and a feminine world of home, children, and family began, in the United States, in the nineteenth century, when increasing urbanization allowed for the creation of two “spheres” of work and home, instead of the communal, collective, agrarian homestead that characterized much of eighteenth century American life.

The role of the middle- or upper-class white woman, hailed as the “Angel in the House,” was to socialize her children, her servants, and her husband in the moral universe of Protestant Christianity. Women were said to be “natural Christians” because they were more emotionally sensitive than men, had greater empathy for others, and in their compassion, were closer in feeling and behavior to Christ.

These traits were said to be innate expressions of the “feminine sex”: their biological difference from men evident in their behavior and contentment with staying in the home. Though men were granted greater institutional power and status than women in this social organization, the opposition between male and female in patriarchy was often represented as not “power over” but rather as “balancing and complementary” sex roles. In other words, the woman’s essential role in society was to morally temper and make acceptable the more aggressive, industrious attributes that were coming to be associated with masculinity.

There was an inherent contradiction between the morality of Christianity, which counseled people to love their neighbor and give generously to those in need, and that of capitalism, which rewarded the ruthless exploitation of others’ labor with the spoils of profit. What was a massive ideological contradiction at the level of the dominant white culture became displaced onto the terrain of biology, or “nature”—the hand of God, visible in the known world. For if God had made men and women in these ways, then white Protestants felt a pressing reason to enact what they saw as a timeless, divine logic.

The need to not only enact, but defend, this social organization became more pronounced as, during the period from the mid century to 1900, the U.S. experienced waves of immmigration from Ireland, Poland, and Russia. Already reeling from the fractures and violence of the Civil War, America was in search of a clear national narrative of its promised future identity. These immigrants were perceived as an economic and ideological threat, a contamination of the white American racial “stock.” (Great Replacement Theory, I’m looking at you.)

Accordingly, Irish and Polish Catholics were depicted in political cartoons and editorials as licentious, alcoholic, and overly sexed, traits responsible for their multiple births and chronic poverty. Russian Jews were said to be neurotic and mentally unstable as a racial group, further threatening American “civilization.”

At the century’s turn, African Americans began to migrate to the Midwest and to Northern cities, escaping the Southern agricultural regions that had been decimated by the economic impact of the Civil War and the poor farming practices that had ruined the soil.

Though affluent white Protestant families were not in direct competition with these migrating families, arguments about the biological differences among the races, with Irish and Black families placed on the bottom rungs of a “divinely ordained” racial hierarchy, reinforced the idea that Protestant success was an inevitable consequence of their moral and racial superiority.

By subtly linking a particular way of organizing the home, and a particular moral ethic, to gender and biology, the white, middle-class Protestant American family could position itself as the most Godly domestic unit and, under the guise of a moral imperative, protect its economic interests from encroachment by the immigrant labor of Catholics, Jews, and following the Great Migration, Southern Blacks.

The smashing success of the film Little Women, nominated for Best Picture in 2020, is an indication of the enduring power of this gauzy representation of family—at least for a white audience. Little Women is a perfect period piece for the current moment, for it at once reaffirms a nostalgia for nineteenth-century domestic ideology, and at the same time offers a tale of a woman’s refusal to hew to its norms. After all, the book’s heroine is Jo March, who struggles to be a paid writer to support her family, and who refuses to marry her best friend.

Most nineteenth-century novels that focus on a female heroine trace her development from girlhood to womanhood. The stories are about triumph over adversity, and a subsection of these novels, known as “sentimental” novels, focus specifically on the role of Christianity in shaping female development. The central task of the heroine in a sentimental novel is to tame her wild temperament. By emulating Christ when she encounters challenges in her life, she can transform from an impulsive, aggressive, selfish child into a generous, empathetic, and sincere adult woman, able to manage her feelings and subordinate her willful nature.

In these stories, the heroine’s achievement of womanhood—and the ending of the novel—is marked by her successful marriage. (If you’ve read Jane Eyre, you’ll know that the line “Reader, I married him” marks the culmination of the plot.) Not much happens in this kind of novel, or a contemporary rom-com, for that matter, after the proposal and wedding.

The tale of Jo March—one of a series of portraits of female development dramatized by each of the novel’s sisters—draws from the sentimental tradition. The telltale sign: her impulsive and willful nature. She has difficulty bridling her own desires, and her ambition pulls her away from her family obligations, all of which are represented as aspects of her “boyishness,” her refusal to become a woman.

There’s an explicit nod to the novel’s sentimental theme in the film, when Jo’s mother sympathizes with her struggles, confessing that she had to learn the same lesson in her own life. It’s clear that part of the reason Jo refuses marriage is her awareness of her own deep ambivalence about this necessary transition. She feels lonely and behind her sisters’ development, and yet there she is, laying out her novel’s chapters on the floor.

It’s been more than 150 years since Little Women was published, and yet many straight white women of a certain class still feel stuck in this bind. Jo’s anguish is a perfect mirror of the unaddressed social contradictions these women are still expected to resolve in their individual lives.

Are women supposed to devote themselves to the care work of home, child-rearing, community tending, and educating others in the morals and values upon which the social order depends? Or should they express their creativity, ingenuity, and capacity to earn money for themselves and their dependents, even if it costs them the opportunity to have an enduring long-term relationship, marriage, or children?

And what does it mean that the denial of abortion care in the U.S. is rooted partly in a romanticized version of a nineteenth-century social order? Why are “women”—with all of the complexities of location, identity, and region that this term overrides—being submitted to policies in the present that are based on a construct that, even in the period in which it was created, represented only a small slice of the American population?

Why are women expected to earn enough money so that the government does not need to provide universal health care, pre-K, or subsidized childcare, and at the same time have to “choose” to stay home, because for so many of even the most privileged of women, the cost of these services is more than they could make at a paid job?

And how has the wisdom and strategy crafted over generations by the women and nonbinary and other folks who have been erased from this conversation altogether been excluded from public conversation, in order to maintain the fiction there is only one way to “be”?

I don’t have room here today to link the slice of nineteenth-century history I just outlined to the rise of the feminist movement, and to the complexities of the fight between liberal and radical feminism about what true, transformational, feminist social change might mean. (That’s coming! Just not today!)

But even this cursory overview of nineteenth-century white, straight gender norms shows that the tension between Emily and Claire, which looks like simple competition between two friends, is rooted in a long history, one that argues that the most moral and selfless choice a woman can make is to get married and raise children, and that women who choose to pursue a career, or to not have children, are somehow selfish and unnatural.

Claire leans in, when I tell her about the nineteenth-century version of white womanhood. She tells me how much she loves movies like Little Women and shows like Downton Abbey; but that part of the reason she thought she loved them is because they were about a world that was past.

She looks into the distance as she mulls. “It’s creepy to think like this. I was raised by a mom who worked full time, my whole life. Most of my friends were raised by single, working moms. My generation was told the feminist revolution, which was our mothers’ concern, made it so we could work and have kids and that this was freedom from restrictions based on sex or gender.

“Plus, my friends aren’t just straight. They’re gay and trans and nonbinary. My gay friends get married, too. I never even knew about this history until you told me about it. But it does explain why my gay friends who are married have to race to protect their current rights from the Supreme Court, and why the Republicans just voted overwhelmingly to deny women contraception.

“But that’s why it’s so creepy. It’s like it’s here, and not here. When I think about me, and Emily, and Jo March, it seems that we’re still there, still fighting about those same things. Like, have we made progress? How do I make sense of this world, which feels like it’s radically different from that time, and still the same?”

I tell Claire that part of the reason I like history is that it can help us see why certain social arrangements can feel like the only way to be. We talk about the fact that there’s both forward momentum and a pull back. That it’s easier for our social order to allow freedom of expression—that in certain parts of the country, at least, people can dress in ways that challenge the gender binary, or engage in relationships that aren’t straight or monogamous—but that these challenges are still happening inside an economic structure that requires a large part of the population to perform labor either for free, or for very low wages, which is not counted as part of the GDP, and which is required, in order to allow for capitalism to pursue a strategy of growth.

“This whole talk is making me sad,” Claire tells me. “I mean, when I think about what we’re saying, then what Emily is choosing makes sense. I get why she got so much approval from her family and friends for planning her wedding, even beyond the fact that she loves her husband. And I get why she’s mad at me, too, for what I’m doing, even though I know she doesn’t have any plans to go to grad school.

“I thought she was lucky to be able to stay home this summer. It didn’t occur to me that her being laid off might have felt like a door closing on a part of her life.”

“I wonder if that makes it easier for you to approach her?” I ask.

“I’m still nervous. But, I see now that it’s not her fault, and it’s not my fault. And I see why we were so mad at each other, feeling so unsupported.

“But I still don’t know what to do. I mean, what am I supposed to say? Like, sorry we’re both stuck in a patriarchal time warp?”

“I have an idea. What about, after you and Emily talk, you get together with your group of friends, and talk about what you learned in your families about womanhood, and relationships, and marriages, and family? About work, and careers, and happiness, and stress? About who you fear becoming, and who you want to be, and whether you think it’s possible?

“Maybe if you and your friends start to talk about these things not so much as individual choices, but instead as answers to questions that structures like patriarchy, capitalism, and white supremacy don’t want you to ask, you will be able to support one another to go against the grain, or figure out how to work together as a unit, to overcome challenges that are too big for one person to solve?”

“Yeah. That makes sense. I think I want the answer. I want this to feel better. But at least this is a place to start.”

If you’ve addressed issues of work and care in your own life, or in your work with clients, please let us know, in the comments. I’d love to hear your thoughts and questions about this case, and the historical context within which it occurs.

Share this post