Photo by Husna Miskandar on Unsplash

Hey there everyone—

This week I want to talk about the Liberation Health Model. The model has been around for twenty years, but I’m starting to see references to it cropping up all over the place. Because the model was specifically designed to bring a wider social context into psychodynamic approaches to healing, it can be a great way of bringing conversations about structural violence and oppression into your practice, even if you’re new to this way of thinking. If you’re not a mental health practitioner, I think this model would be equally useful for community organizers, and also would help people working in businesses or governmental agencies initiate a discussion about a social problem that doesn’t rely on the solution being limited to individual actions.

The word “liberation” in the model honors and acknowledges the work of liberation theology, out of which grew liberation psychology, a way of thinking about healing that was practiced by Ignacio Martín-Baró, a Spanish-born Jesuit priest who trained in psychology at the University of Chicago. Martín-Baró practiced in El Salvador and wrote about the relationship between the social conditions of the most oppressed peoples in Central America and the ways their oppression could be traced to the oligarchical class, which was itself influenced by the ways the U.S. was treating Central America as a satellite state.

Martín-Baró was concerned that the individualist focus of therapy could encourage people to adjust to the status quo. Psychology’s attention to individual behavior, and the ways behavior is seen as an expression of the individual’s consciousness, keeps both the problem, and the solution to the problem, inside the arena of the self.

If consciousness is examined as an expression of the self, and not as something that is actively engaging and at the same time a product of its social conditions, then both the understanding of the problem, and the solution to the problem, will stop at the individual. The person in therapy will not ask questions about the ways his social context is impacting his behavior, and most importantly, he will not ask himself how he might participate in social change.

The work of psychology, Martín-Baró wrote, should be that of concientización, a term he took from the philosopher and educator Paolo Friere. Friere, who was born in Brazil, is responsible for a way of teaching he named pedagogy of the oppressed—he wrote a book of the same title, which outlines his method.

Friere was tasked with the project of teaching the campesinos—the landless workers who labored on massive estates—to become literate. But because “literacy” was not something that the people themselves had identified as a need, Friere decided that advertising “literacy classes” wasn’t the way to go. Instead, he invited the people to join in “culture circles,” where they would get together to talk about how they understood the world and what changes they might want in their lives.

Friere argued that the pedagogy of educational institutions was based on what he called the “banking method.” The educator, standing at the front of the classroom, is literally positioned by the architecture of the room as the holder of knowledge, the one who has more standing than his students. The teacher “deposits” his wisdom into the empty heads of his students, who are willing and passive receivers of his deposits.

The banking method denigrates students by positioning them as receivers, rather than collaborators, in the production of knowledge. Education thus reinforces a power dynamic that keeps students feeling like they are lesser than those who are educated, and that they have to wait until they have standing and status before they can speak up, or take their own experience and knowledge seriously.

Friere decided he’d create a new model, one based on concientización—developing the critical consciousness of the people. Friere’s method was incredibly successful, and the people he worked with learned to read in as little as forty-five days. The government, excited about his success, asked him to create a national program, targeting five million people. But before the program could be put into place, a military coup overthrew the government and Friere had to flee for his life.

Inspired by Friere, Martín-Baró argued that psychology could also take as its goal that of concientización:

We are proposing that the task of the psychologist must be to achieve the de-alienation of groups and persons by helping them attain a critical understanding of themselves and their reality. . . . psychology has not addressed the question of the mechanisms that block consciousness of an individual’s social identity, causing him or her to act like a dominated being or a dominator, an oppressive exploiter or a person who is marginalized or oppressed.

Liberation psychology allows us to ask an important question: if the banking model teaches people to be passive receivers of knowledge, could we see the practice of therapy, of social services, of “helping professions” as that of creating a similar power dynamic between therapist and client, expert and patient? I don’t have time here today to get into the history of psychoanalysis, but when you read Freud’s case studies, you can see that even though he’s not directly “telling” the patient what’s happening, the way a teacher tells the student what they should study, the power dynamic between Freud and the patient situates him as the one who sees, who knows, who has the skills of interpretation the patient lacks.

But here’s the thing: the mental health practitioner does have knowledge that the client lacks: she has training; she has years of practice; she has her own life that she’s lived. She is tasked with bringing some sort of use value to her clients. But if she reenacts the banking model, she risks disempowering her clients; she risks shutting them down, filling them with terminology and treatment interventions. She substitutes her own knowledge and agency for that of the client, who must determine her own understanding of what is needed to solve the problem, in order to feel empowered enough to make the change. At the same time, however, if the client could fully determine what to do next, without the aid of the therapist, she wouldn’t be in the room.

This complex interpersonal dynamic is why overt conversations about power can be so crucial to the work of liberation psychology. The therapist is situated, institutionally and structurally, as the one who knows; the client is situated as the one with the problem. The “collaboration,” between them, if it occurs within this framework, is that of the therapist gently educating the client about the best way to proceed, working hard not to dominate, but at the same time, “helping.”

There’s a lot of impetus, professionally, for the therapist to demonstrate her usefulness to the client. There’s also a soothing aspect to diagnosis and treatment: it narrows the scope of the therapist’s responsibility; it gives her the fiction that there’s an answer to complex problems; it helps her not fall into the abyss of existentialism, hour by hour; it helps her maintain hope. It also creates a power dynamic that subtly or overtly—depending on the nature of the institution—disempowers the client.

Martín-Baró writes that concientización demands more from the psychologist, because he must enlarge the scope of what is discussed in therapy. The psychologist must “produce an answer to the great problems of structural injustice, of war and national alienation, that overwhelm our peoples.” The work of the psychologist is to “make a contribution toward changing all those conditions that dehumanize the majority of the population.” Now this essay is a translation, and I don’t know what he means by “answer” in the above quotation. But I’m guessing he means “answer” in the philosophical sense—how is it that we have this social problem, and how is it that this problem can be seen as available for change, rather than an intractable aspect of life.

I think that if the mental health practitioner opens the scope of conversation as he suggests, the idea that there is one answer, one intervention, one diagnosis for a mental health condition, goes out the window. This means that both the therapist and the client have to become comfortable with ambiguity, uncertainty, fear, and loss. They have to grieve, together, the suffering that so many people are enduring. And in that lack of clear direction, of a simple solution to a problem, collaboration between the two becomes a necessity, rather than a concession the therapist makes to the client at her own discretion.

Martín-Baró was murdered for his work. He was gunned down by a Salvadoran death squad. Friere had to go into exile for sixteen years because of how and what he taught to people who were oppressed. Those who sought to maintain their power, and to maintain the status quo, saw how effective both of these men were in helping people to access collective power and understand their circumstances, and they didn’t like it, at all.

So when you see the word “liberation”—liberation psychology, liberation health—you want to think about people coming together to discuss the social context that influences their world, and to help one another see and describe the structures of violence and oppression that make it difficult for them to access and engage their individual and collective power. By doing so, they will be encouraged to stop blaming themselves for “failing”; they will start to question the source of their shame; they will stop, as Martín-Baró put it, “acting like a dominated being or a dominator.”

When Dawn Belkin Martinez, a social worker from the United States, started practicing, she wanted her work to include attention to power, culture, and context. But her education in social work trained her to see policy and social structures as “macro” work, and her work, “clinical work” as “micro” in scope, focusing on individual behavior in the context of self and family.

Since she couldn’t find the training she was looking for in the U.S., she went to train with Friere. Luckily for her, when she came back to Children’s Hospital Boston where she was working, the people there were very interested in what she learned, and encouraged her to design a model of healing that drew on Freire’s method. Martinez is now a Clinical Associate Professor at Boston University’s School of Social Work.

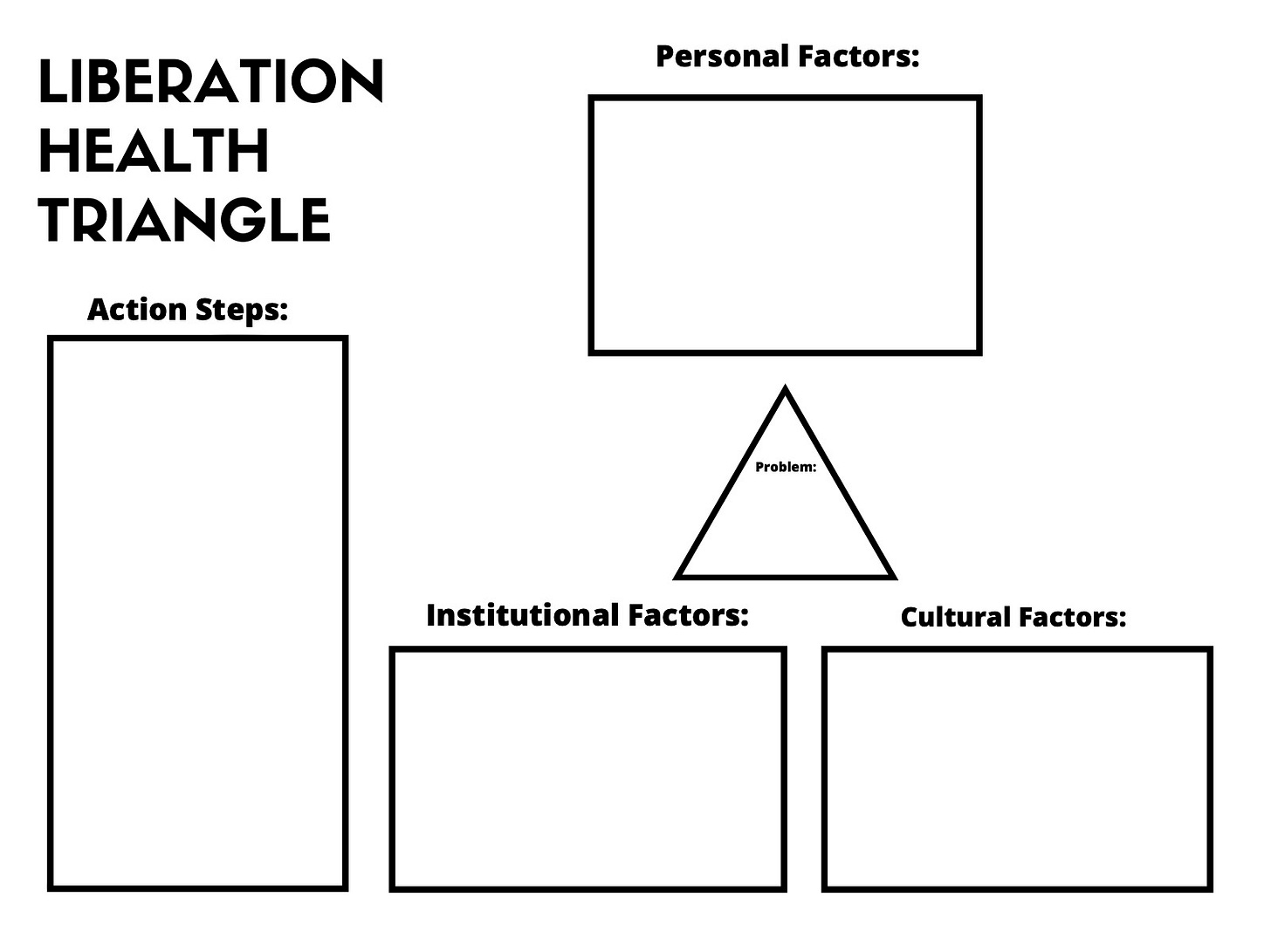

The first step in the Liberation Health Model is for the client to put the problem in her own words. Her own analysis and language is then placed in the literal center of the diagram that will be used to determine the appropriate response to the problem.

When the person who is suffering is asked to put the problem in her own words, she is engaging in concientización. The story of the problem is then put in its larger context: that of diagnosis and treatment; that of institutional responsibility; and lastly, that of culture. By highlighting the diagnoses and treatments that have been generated by institutions about the client; by identifying the cultural narratives about the client’s identities, class position, ability, and capacity for change, the client can start to place her own problem within a much larger context. There are now practitioners all over the world practicing liberation psychology, the Liberation Health Model, and other lines of practice rooted in the Healing Justice tradition.

Here’s a short video about the Liberation Health model, to get you started:

And here’s the template for healing, which can be downloaded off the Boston Liberation Health website:

If any of you reading this are already practicing with this model, please let us know how it’s going in the comments section. What struggles have you encountered, using this approach? What has surprised you about using it?

Also, here are some questions I use myself, when I’m trying to broaden my scope of inquiry about a problem, whether it’s personal or collective:

Whose knowledge (What is the source of the information; what “counts” as knowledge?)

Whose power (Who is said to be in the power position; is power circulating through the group, or is it concentrated in a hierarchical orientation?)

In what context (What are the unacknowledged assumptions about the problem and the best way to fix it? Where does the problem begin and end? What happens if the context is made larger than the individual or the group?)

To whose benefit? (When you think about the proposed solution to the problem, who will gain from having it solved in this way, and whose needs are excluded?)

To what end? (What is the ultimate goal of the solution? Is it a temporary solution? Does it silence further conversation and analysis? Is it open-ended or closed?)

I also want to thank Shimon Cohen and Charla Cannon Yearwood for their current CE course, liberatory practice, offered through Columbia University’s School of Social Work, part of a fantastic series of courses they’ve been offering all year on how to bring anti-oppressive practice to the field of social work. Shimon, in addition to his work as a teacher and activist, is the creator of the incredible podcast Doin’ the Work (dointhework.com) and Charla, in addition to her teaching and research, is the founder of Connected in Community (connectedincommunity.org) a group practice working in service of community liberation.

If you get a chance, read Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Writings for a Liberation Psychology.

Thanks, as always, for reading and listening!

Stay safe out there this week!

xo

Rebecca

Share this post