Photo by Mathias Reding on Pexels

So. This past week was one of those weeks where what I was going to talk to you about kept shifting under my feet. I started the week by working on a piece for you on boundaries.

In the case of the boundaries post, I decided to look at what happens when we take a concept that’s pretty much taken for granted as a “good” therapy practice, and ask what happens to that concept when we move out of the zone of the individual, and overlay the lens of structural power. I thought it was going to be a fairly simple piece. I was going to ask us to notice that expanding the context in which a boundary is set can introduce new ways to understand and talk about boundaries with clients, and anticipate the impact of oppressive systems on clients’ attempts to set boundaries.

But writing the piece wasn’t simple. As soon as I put the interlocking structures of patriarchy and white supremacy “over” the generally received wisdom of what a good boundary looks like, I started seeing things, and asking questions. Most of my questions ended up showing me the field’s unacknowledged assumptions about what a boundary “is” and what it’s “for.”

One thing I noticed was that lots of the authors writing about boundaries used metaphors of land, property, rights, and ownership of the self to describe why a person might need or want a boundary, and why they should view setting a boundary as an act of healing or self love, even if the other party accused them of being aggressive or selfish.

So then I asked myself why the “self” that’s setting the boundary is conceived of as a form of property, and what that might mean, in the context of the U.S. history of who can and cannot own themselves, who is owned by another, who has 3/5ths of a self and whose self had the franchise and for how long.

Historically in the U.S., is it only the white self that has had enough “property in the self” to assert a boundary? Is that still true, in certain contexts? How do the conversations about property in the self and boundaries operate in the context of the overturning of Roe v. Wade?

It seemed like most of the writing on the self relied on a European concept of selfhood, steeped in concepts of land and property. It made me wonder what Indigenous models of the self look like, given the fact that Indigenous cultures have a completely different relationship to the earth than Europeans.

And what about communitarian cultures, which subordinate the needs of the individual to the community, or don’t even talk about selfhood on the level of the individual at all?

Another thing I noticed, as I reviewed the literature on boundaries, was that so much of the writing talked about how to “set” the boundary, but didn’t address the power relations between the two parties. Does that mean that the two people who are impacted by the boundary are thought to be equals? Or that the act of asserting the boundary eliminates power differentials? Are two parties ever equal, in their structural or institutional power?

And if they aren’t, why are we telling people they can assert a boundary and expect a positive outcome? Why are we assuming that you can protect yourself by setting a boundary, when in certain contexts, that act could result in institutional reprisal or interpersonal violence? What are our (“our,” being the “field’s”) assumptions about power, how it works, who has it, and what to do about it?

Boom. Game over. My head was buzzing. No way that piece was going to be ready for you in a few days.

I’m starting today’s post with my story for two reasons. First, because I want to say that I’m in here with all of you, struggling to figure out what it’s going to take to get the field of mental health, and therapy more specifically, to become accountable for its rootedness in white supremacy. I’m not outside this struggle, with answers to dole out every week. I’m in here with you, frustrated, overwhelmed, searching.

And my story about writing that boundary post, I’m sorry to say, is itself a reflection of how even as I’m working to identify and talk about white supremacy, my very approach to writing the post was an expression of whiteness.

I thought I could talk about a concept, put a lens on it, and start a discussion about how to “add in” patriarchy and white supremacy. I thought it was fairly simple to juxtapose what it means to talk about a boundary from the perspective of an individual and a structure. I thought I could do all that in a week.

And what happened instead was that as soon as I started introducing whiteness into the conversation about boundaries, the entire concept started to unravel, unwind. Within thirty minutes of reflection, I was asking myself if the idea of a boundary needed to be jettisoned, altogether.

I know very well that you can’t “add” a critique of white supremacy to an already-existing field and expect anything to change. But I thought I could retain the idea of a boundary and complicate it, by “adding in” a conversation about whiteness, patriarchy, and power.

So I’m telling my story to say that this project of talking about patriarchy and white supremacy in the field of mental health is one in which I am going to be constantly working to inhabit a transformative consciousness, and repeatedly falling back into the assumptions and ideologies upon which the field is based.

I fell prey to whiteness in the way I approached the topic, in the speed at which I expected myself to move, in the frustration and brain fog I experienced, when I had to confront, again, the depth of the roots of whiteness in the practice of therapy. And in that moment of frustration, I thought I had nothing to offer you. If I didn’t have a complete and coherent way to talk about boundaries, what business did I have, trying to write these newsletters. And I don’t mean that in a drama queen kind of way. I mean, I really felt for a minute like I had nothing of value to say.

There’s that all-or-nothing thinking, and that idea that what white people have to offer is analysis, headiness, a totalizing framework of understanding. That my emotions were a consequence of my failure as a writer, rather than a reflection of what it feels like, in this moment, to want change to happen, to want pain and oppression to cease, and to know that real change is slow, inching, uncertain, unknown.

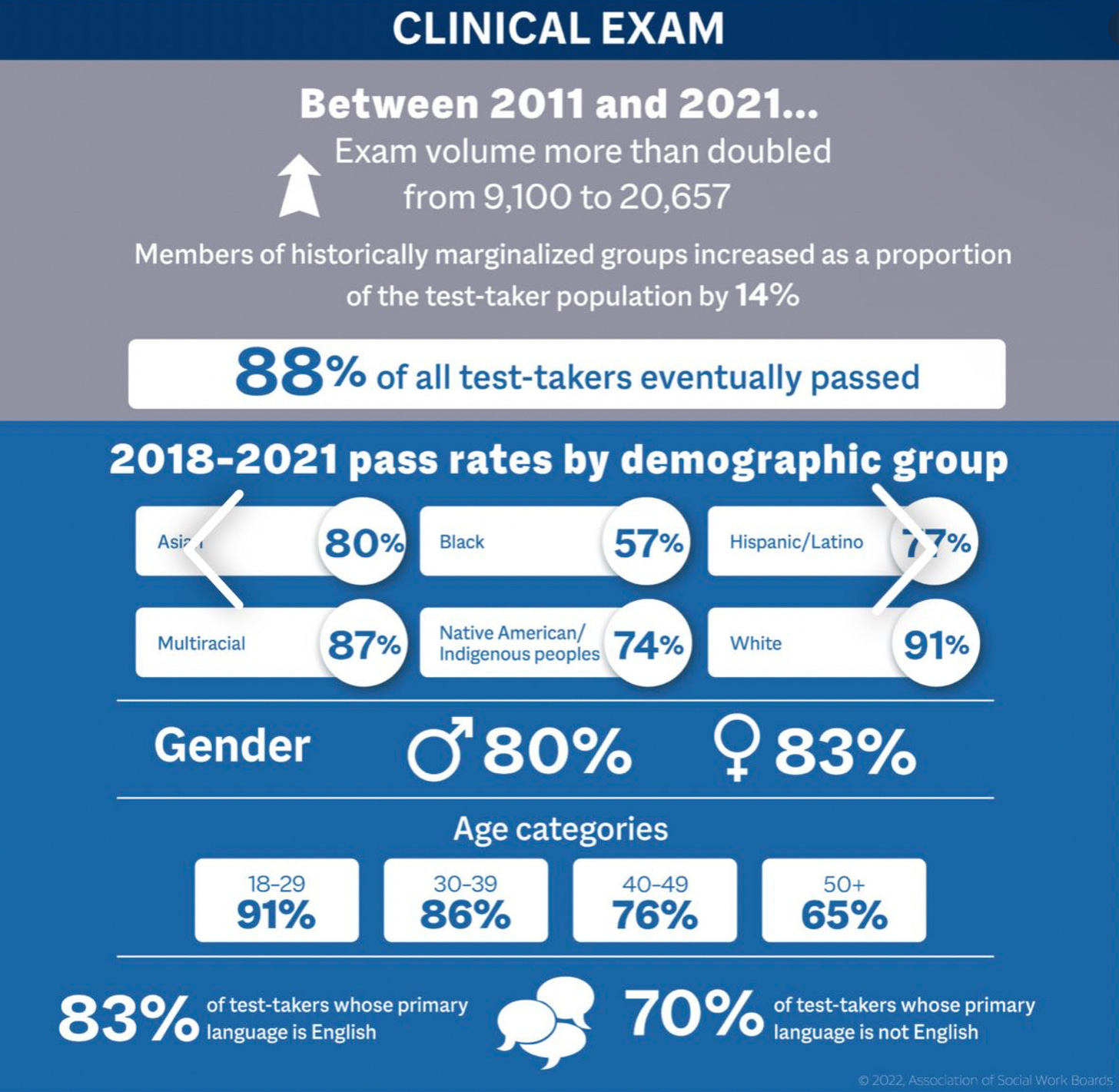

Two days after I hit the wall on the boundaries piece, I learned the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB) finally responded to pressure and published the stats on their exam pass rates in this report. The results are horrifying and unsurprising.

It should be noted that the data ASWB chose to illustrate in their graphic was the eventual pass rate for the exam. Buried in the report was the first-time pass rate for the exam, which is worse. The Illinois chapter of the National Association of Social Workers noted, in their response to the report, that “the report mentions that first-time pass rates are better for determining bias; however, the information was written to highlight eventual pass rates, which skews the results.”

On Twitter, Isabel Vee posted a revised graphic, which crosses out the eventual pass rates and substitutes the actual first-time pass rates for the exam:

The response to this report on Twitter was explosive. Already today, Monday, the first business day after it was produced, there is movement energy to challenge the ASWB and the NASW to address the role of exams and licensure in the practice of therapy.

ASWB’s report includes a three-page “discussion” of their data. The discussion doesn’t name the institution’s, or the field’s, rootedness in whiteness, and the likelihood that the test questions are an expression of whiteness as a way of being.

It doesn’t acknowledge the longstanding arguments that the test is biased, and should be rewritten to include subject matter that is rooted in Afrocentric models of healing, Indigenous practices, and other healing modalities. It doesn’t explore what qualifies as “social work knowledge” or raise questions about how accreditation processes and quantitative research produce what counts as “knowledge” and “evidence,” or describe what knowledge is used as the source of the current exam questions.

I’m grateful to Alexandria L, who reposted on Twitter last week this important conversation about how the exam might be revised:

What ASWB does acknowledge is the impact of structural violence on the test takers themselves:

Census data have consistently shown that individuals from historically marginalized groups disproportionately experience socioeconomic hardship related to lower household income, higher poverty rates, inequities in educational resources and attainment, and lower rates of health coverage, wealth, and home ownership (Shrider et al., 2021). Accordingly, historically marginalized groups may be more likely to experience challenges in the period leading up to exam administration, including but not limited to access to comprehensive, accurate, and effective exam preparation resources; sufficient time or availability to prepare for taking an exam; and adequate financial resources to pay for the exam.

To read this text is to infer that the ASWB sees itself as outside of the effects of patriarchy and white supremacy, and the test takers themselves, as individuals, as inside these structures. It is the test takers, they say, who may be operating out of “stereotype threat,” being so anxious about proving themselves “exceptional” in the face of stereotypes about their racial or ethnic group, that they throw the test. It is those on the receiving end of racism and structural violence, this text notes, who are impacted by these systems. But those who are racialized as white, as the universal, invisible “norm” against which all others are racialized, are somehow outside these ideologies.

What ASWB is doing, in this paragraph, is displacing its responsibility to address its institutional expression of white supremacy, the structure, onto Black people, as individuals, who experience the impacts of both racism and white supremacy, as individuals and as a group.

Following this logic, it is Black people who “need resources” to fix this, not the institution that created the test, which is fundamentally flawed. White institutions can therefore look for “resources”—money, grants, mentors, etc.—to help those who can’t pass the test. They can continue to be the good guys, making up for inequality, and avoid having to engage in self-scrutiny or institutional transformation.

ASWB doesn’t acknowledge that to begin to address the legacy of white supremacy in the field, practice, and management of social work—and by extension other forms of therapy, case management, and social services—that every institution will need to become fluent in how to understand and combat white supremacy, the structure, rather than retaining a focus on racism, one engine of acts committed by individuals.

I fear ASWB is not only trying desperately to hold onto its institutional authority—and the money it makes off the test—but also going for the quick fix: the overlay, the frantic attempt to paper over its own expression of whiteness. I fear it is simply, in its current incarnation, unable to imagine a process of slow, determined, halting excavation of its epistemologies, its practices, and its assumptions about what professionalism “is” and what therapy “is.” I fear it is going to continue to avoid engaging in a process of deep self reflection and transformation that could serve not only the test, but the broader profession itself.

The exam that prevents Black people from practicing therapy