Illustrations by Stef Koehler of Green Crane Innovation

The lead article of the August 22, 2022 New York Times’ digital homepage “What are the Real Warning Signs of a Mass Shooting?” rebuts the common story that it is mentally ill people who engage in mass shootings, and that to prevent them, we should increase the funding for mental health. The author, Shaila Dewan, interviewed a number of experts, all of whom stated that there are a number of “warning signs” that are better predictors of mass shootings than a person’s mental health diagnosis, or their involvement in the mental health system.

This article is useful for a number of reasons. First, it provides a more complex and multi-causal framework for understanding mass shootings. It also works to challenge the stigma surrounding mental health diagnoses—particularly delusional disorders—by demonstrating that even when a shooter is psychotic, the hallucination or delusion is not the primary impetus for violence.

And though Dewan doesn’t explicitly address the old right wing saw “guns don’t kill people, people kill people,” it’s clear that by expanding the interpretive framework with which to predict and respond to the threat of mass shootings, she’s seeking to complicate the argument that mass shootings are unpredictable outbursts from deranged psyches, and therefore impossible to prevent.

I thought it might be fun to take this excellent article and ask what more we might see if we overlaid a structural lens on the question of predicting mass shootings. What is illuminated? What questions can we ask that aren’t already being engaged? What solutions might be hidden when the focus is limited to the individual’s social context or psychology, but become visible when a structural lens is in play?

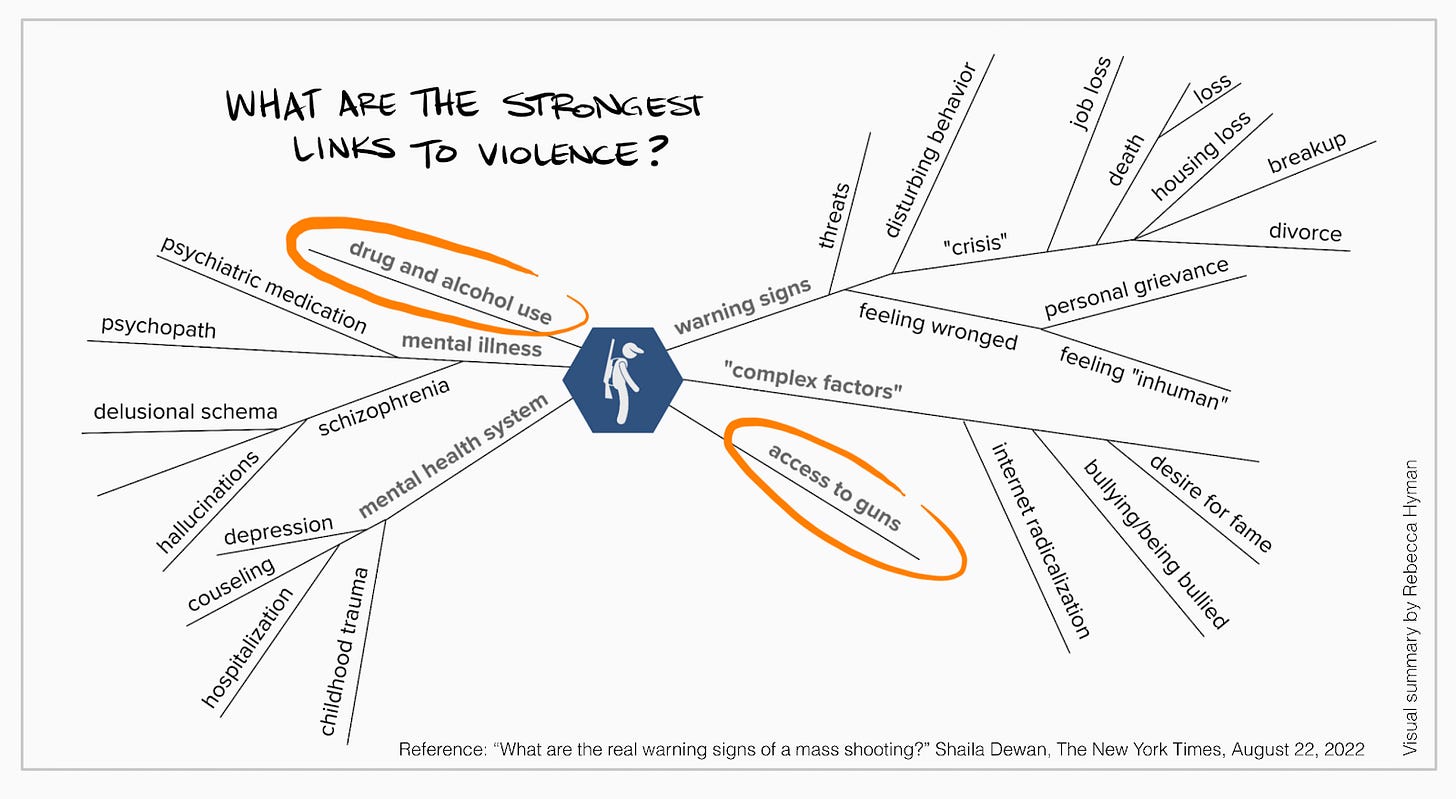

And because the elements of this original article are complex, I thought it would also be fun to translate the article into a visual mind map, instead of a written summary. So—here’s a mind map of my summary of the article. You’ll see that I’ve put the “mental health” argument that Dewan is rebutting on the left hand side, and the new information she’s outlining in the article on the right:

Dewan’s experts stated that an individual’s involvement in the mental health system, or diagnosis with a particular disorder, aren’t necessarily the best ways to predict a mass shooting event. As fifty percent of Americans could be said to have “mental health issues,” the experts argued it is impossible to create a clear correlation between a person’s having mental health problems and their likelihood of committing mass violence. And then there’s the question of whether mass shooters are “delusional”—if their violence is in response to some internal schema.

According to the Violence Project, though 30% of mass shooters have experienced psychosis, only one-third of that 30% could be said to be responding to the psychosis itself in committing a mass shooting. The majority of people who experience delusions or hallucinations, moreover, do not commit violence of any kind.

What, then, do the experts say are the strongest links to mass violence?

It would seem that if substance use and access to guns are the most strongly linked to predicting a mass shooting, that these should be the main focus areas of our efforts of prevention. But they aren’t.

The experts cited in the article say that rather than looking for mass shooters in the rosters of those with severe mental illness, we should look for the “warning signs” that could predict a person’s propensity to plan and execute a mass shooting. The person might have a series of beliefs that “leak out” in their conversations with others, or their online postings. They may have experienced a series of crises in their home, work, school, or personal life. They may have been bullied, shamed, or harassed by their peers.

Because the point of the article is to undermine the thesis that mental health disorders are predictive of mass violence, it stops short of fully investigating the question of how to prevent mass shootings. The experts did provide some suggestions, however:

Training programs can help others develop threat assessments, by looking for patterns of behavior and the presence of crises in people’s lives.

Peer and social support can counteract the isolation and self-loathing that can occur in response to bullying or abuse.

Mental health treatment can be a component of care for those at risk.

Funding for alcohol and drug treatment should be increased.

These solutions are all useful, and expand the scope of prevention. I noticed, however, that though substance use and access to guns are the strongest links to mass shootings, the expert advice was only to provide more funding for substance use treatment.

It made me wonder how we could better tailor substance use treatment to prevent mass violence. I also wondered what strategies could be developed to prevent access to guns, beyond passing laws?

But what most stood out to me what the fact that there were a number of issues addressed in the “warning signs” and “crisis” branches of the mind map that were not addressed by the experts’ proposed prevention strategies.

It’s these elements that we’re going to examine for the remainder of this post. We’re going to ask the question: can a structural analysis of violence help us understand these elements? And if so, how might that analysis offer an additional way of understanding mass shootings?

Early in the article, Dewan states: “America’s mass killers fit no single profile and certainly no pattern of insanity—many, if not most, had never been diagnosed with a serious psychiatric disorder.”

That may be true, and yet: every single incident of a mass shooting cited in the article was committed by a man.

Why, then, was there no discussion of the relationship among sex, gender, and mass shootings by Dewan or by any of the experts? (Notice my interest is not in any particular man, but rather the construction of masculinity by patriarchy, the structure.)

And why are sex and gender not considered categories that could be explored as part of a profile of a prospective mass shooter, given the fact that the Violence Project’s data indicates that: “Of the 172 mass shooters studied, only four were women. In two cases, the women acted in partnership with a man. While the difference in numbers between female and male mass shooters is stark, it was represented in all U.S. homicides in which 80% to 90% of offenders in a given year were men.”

I also wondered what percentage of the shooters were white. The Violence Project database states that “The stereotype of a mass shooter is a white male, however, white people account for just over half (52%) of all mass shooters. The Violence Project classifies each mass shooter as one of six different races or ethnicities.”

It would seem then, that the strongest link of all, in terms of predicting a mass shooting, is that the shooters are men. We could then ask: what it is that links all of these men, and what it is that makes men respond to all of these warning signs and crises by engaging in mass shootings?

We could also turn the question around, asking: why is it that women do not engage in mass shootings? Why is it that only 10 to 20% of homicides are committed by women?

The experts state that crises are precipitating factors, contexts that could tip a person into planning and executing a public shooting. But if we look at the branch of the mind map labeled “crisis” we will see that all people, of all genders, can experience these crises, and can exist in contexts in which they are bullied, or shamed, or abused. But not all people respond to these contexts and crises by engaging in a mass shooting.

Why, then, don’t the experts ask if their analyses only apply to men? Why aren’t they acknowledging that their framework should be asking questions that help them understand why it is that men respond to these contexts in a way that is different from everyone else?

Something, that is, is already preventing everyone else from shooting. What is it?

I wondered what would happen to our analysis if we shifted our thinking from looking at the characteristics of individuals—or even of groups of individuals—to instead asking about the structures, the network of ideologies, that saturate the meaning making and organization of the dominant culture, so much so that they can seem so natural, so inevitable, that they are somewhat invisible. They are so much the air we breathe, the water we swim in, that they don’t appear as elements to be analyzed in relation to individual and group behavior.

And if we look at the NYT article, and the Violence Project database, we will see that neither space of investigation moves from the level of the individual to the level of the structure, either in their data collection, or in their hypotheses about how to understand and prevent mass violence.

What happens when we shift our lens from men, the group of individuals, to the structure that impacts all of us, but that values those individuals and traits that are coded as masculine and de-values those individuals and traits that are coded as feminine? The system, that is, of patriarchy.

What happens to our capacity to predict—and more importantly, to prevent—mass shootings, if we include an understanding of patriarchy in our conceptualization of the mass shooter? And is there something that might unite all of the elements of the mind map that are left out of the experts’ ideas about how to prevent a mass shooting?

The feminist philosopher Kate Manne has written extensively about the relationship between patriarchy, misogyny, and mass violence. In her first book, Down Girl, she writes that men are socialized by patriarchy to expect that women will devote their care and attention to men, and to expect that they will receive this care as a matter of course. In turn, they want to conform, as closely as possible, to the definitions of masculinity that are hailed in the dominant culture as indicative of patriarchal success: money, status, beautiful partners and children, confidence, and a particular male physique.

When women are perceived to be refusing to provide this care—either because they are focusing their time and energy on their own ambitions, or because they are providing it to other men—they can respond with violence.

In her second book, Entitled, Manne explores not only the ways that patriarchy demands female care be provided to men, but to the assumption on the part of some men that they are entitled to respond to their deprivation of female care, attention, sexual desire, and companionship with outrage and at times, mass violence.

The saturation of the dominant culture with patriarchal norms, that is, could be creating a context of expectation: if, for complex reasons which may or may not in themselves be linked to patriarchy, men don’t receive this expected care, they can respond with outrage, internalized self-loathing, and contempt, both for the women who are shunning them, and the men who have received the entitled care they desire and can’t have. Thus, some shooters will target women with explicit hatred, but many will kill both women and men, out of a sense of shame and rage for their loss.

If we have this lens of patriarchal entitlement in our minds, and then return to the mind map, we can see that what appear to be distinct, separate elements that can predict a mass shooting can be united under an idea of the loss or denial of “patriarchal entitlement”

Feeling wronged

Personal grievance

Feeling “inhuman”

Being bullied or shamed

Kate Manne has identified these behaviors and beliefs in the content of internet chats and threads, and also on forums that focus on involuntary celibacy (or “incels”), spaces that reinforce the patriarchal construction of masculinity as an ideal to which men should aspire. She has also demonstrated that many who do not or cannot conform to this ideal respond to this perceived loss or failure with self-loathing and shame.

It is possible, then, to add “internet radicalization” to the list of factors included in patriarchal entitlement and its denial or loss. And the “desire for fame” could be a way of compensating for a feeling of abasement or humiliation, or of being robbed of one’s expected receipt of patriarchal valuation and success.

How, then, might the prevention strategies outlined in Dewan’s article be augmented by including Manne’s notion of patriarchal entitlement as a source of violence? How might we extend this thinking by creating related questions: Is the expression of rage and power in the planning and execution of mass shootings correlated in any way to the denigration and abuse that many men receive if they express the “feminine” traits of vulnerability, grief, fear, confusion, and hurt, which mark them as “inhuman” in terms of accessing a particular version of masculinity?

How does white supremacy, working in concert with patriarchy, make certain forms of masculinity more linked to status, success, and wealth than others, and make some men feel hopeless about attaining these forms of material and social standing? Why do some men kill women they identify as non-white, if they feel conflicted about their need and desire for them?

And lastly, how might we use these questions to illuminate the presence and impact of patriarchy in all of our lives, asking about its effects on people of all genders, beyond the frame of mass violence?

Though these questions are just a start, they demonstrate the ways including an analysis of structural violence can help us to better understand and solve problems as challenging and complex as why it is that mass shooters are almost exclusively male.

Share this post