The day 40 clients and therapists came together to create an alternative to psychiatric diagnosis

Introducing: The Power Threat Meaning Framework

Photo by Tima Miroshnichenko on Pexels

Imagine this.

You’re a therapist. It’s Monday, 10 am. Your new client comes in and sits down in the large royal blue chair, running her fingers through the nap, making patterns as she talks. She’s got shoulder length blond-red hair, blue eyes, a rounded face, a few freckles. She’s wearing a cream colored cotton sweater and jeans, with a rope necklace at her throat. After asking you if she can take off her shoes, she sits cross legged in the chair, holding her cup of tea in her lap.

She tells you she’s not sure if being here is right. She has a three year old and a twelve month old and time is tight. She had to pick: the gym, therapy, a creativity class, or free time to herself. This is it: her only time in the week when she’s not taking care of her kids. You nod sympathetically. You say you won’t be offended if she picks something else. She breathes out when she hears this. It’s so hard to know, she says.

She has a partner: he’s been really supportive. He used to come home and turn on the TV or play a video game and wait for her to make dinner. Now he plays with the kids, giggling and rocking them so she can work in the kitchen, out of view.

When you ask why she came today, she pauses. She says she’s been having a hard time focusing. She’s so used to being interrupted by the kids that she’s edgy when she has a few minutes to herself. She doesn’t know what to do. Today she prepared too early for the session, then wandered around the house and left too late.

She looks out the window at the leaves turning. She says sometimes she just feels blank. At the end of the day she often can’t remember what happened at all. When she talks, looking away into the distance, her face changes. When she’s looking at you, answering your questions, she’s eager, smiling, eyes locked in. When she tells you about her time alone, her mouth settles into a completely different expression. She’s looking into a place you can’t know yet.

You ask if she’s able to sleep, if she’s eating regularly. She’s waking up in the night, she says. Busy thoughts about nothing. It’s hard to keep track of your own eating schedule when you’re taking care of little ones, constantly cooking and cleaning up after them. She knows she eats dinner, because she makes it for the two of them. When you ask if she knows what she’s hoping to change, she looks at you like she’s failing a test.

When she gets up to leave she asks the name of one of the plants on the bookshelf, touches the clay pot on the table by the door, looks at the throw rug on the floor, and then up at you. Her body holds a question she’s not asking. You say It’s nice to meet you. I’ll see you in two weeks.

That Friday your billing person calls and says you forgot to give a diagnosis for your new client and she can’t bill unless you do. You think back to the conversation. She says she has difficulty focusing. Poor sleep and appetite. Low motivation outside of caring for two kids. Questions of meaning and purpose. These could signify the onset of depression.

But she was also second guessing herself, thinking your questions demanded a right answer. Her sleep is interrupted by rumination. She’s waking up too early, a sign of anxiety. She couldn’t remember being hungry, or if she ate during the day. Her body seems to be revved up, but her relationship to time feels like everything is slowing down, grinding to a halt. Perhaps she’s suffering from anxiety more than depression? There are anxious depressions and lethargic depressions—perhaps the question is which kind of depression is this?

But what about the missed time? Is that about days full of repetitive tasks, or is she too scared to let you know that she’s dissociating, that the missed time isn’t about boredom but instead a losing touch with reality altogether? What if she has a significant trauma history and she’s trying to figure out if now is the time to open the door to her past? If she’s home alone and losing chunks of time, are the kids safe?

You give the biller the code for depressive disorder and write rule out anxiety in your notes to yourself.

Three months later she tells you her partner lost his job and now that he’s home she’s feeling watched while she takes care of the babies. When she stopped in at the coffee shop on a walk with the stroller she saw a flier for an accountability group for people trying to find a new job. She told him about it. Now that he feels bad about himself because he’s not working he’s been critical, she says, asking her to explain why she’s doing things in a particular way. She’s been doing it that way the whole time, he just didn’t know. He said he’d think about the group. They have savings, but not a ton.

At the end of the session she tells you they have insurance coverage for the next month, but then her coverage is going to end. You tell her you’re on the Medicaid panel, but she’s going to have to apply, or your therapy is going to be interrupted. You ask if she’d be willing to apply for SNAP, to get money for groceries. She says other people need it more than her; she’ll figure it out.

It’s two months later and she comes in with red eyes. She’s looking at her lap. She says she can’t believe she did this, but a few weeks ago she was up in the night and she took a kitchen knife into the bathroom and made a few light cuts on her thighs. She used to do that when she was a teenager, after bad fights with her mom. She thought she was past it. She thought she could get away with not telling you, but the urges to cut again are getting worse.

She’s been panicking about the money in the bank account going down and feeling like she can’t have anything of her own. Even though they can’t afford it, last week when she was out with the kids she rushed into Anthropologie and bought herself a shirt, full price, that she couldn’t afford even when her partner was working.

She doesn’t want to return it. She can’t wear it, because he’ll see. It’s in her closet and she takes it out sometimes and runs her fingers across the fabric. It’s white ground, covered with red poppies. The material is so light that when she waves it in the air it reminds her of summer; the way the petals look in the wind.

The biller calls again, asks if you want to change anything in the diagnosis of your new client. You look at your list of new behaviors: impulsivity. self harm. relationship stress. possible controlling behavior or domestic violence. economic insecurity. loss of sleep. Some of these behaviors might indicate your diagnosis is off.

The self harm, the loss of time could indicate a kind of dissociation that’s closer to borderline personality disorder, or PTSD from a trauma she hasn’t disclosed, than depression. But what if the increase in impulsivity is the first sign of a manic episode?

The possible domestic violence and economic insecurity don’t qualify as diagnoses, because they aren’t mental health disorders. There are V codes and Z codes that you can use to record the stressors she’s facing. But the insurance company won’t pay for V codes, because they reimburse for the treatment of mental illness.

Is she getting sicker? Is she starting to trust you enough that she can show you she’s been ill for a long time, but wanted to appear more functional than she is? Are her circumstances so different, now, that she’s less functional, not because she’s ill, but because her stressors are overcoming her capacity to cope?

You’ve only been working together for five months, and she’s had to cancel a few sessions when the kids were sick, which means you’ve had sessions where she’s just filling you in on the details of her life; there’s not much time to process. She’s had to leave a lot out, just to tell you the major stuff. There’s so much you don’t know about her life, her relationship history, the larger context for her current situation.

You’re supposed to know what’s really going on, so you can provide the best support. You’re supposed to have a sense of what’s coming, so you can figure out the most accurate diagnosis and treatment. You’re supposed to trust her, take at face value what she’s telling you, what she says she wants.

You’re supposed to see what she can’t, so she can get a wider perspective. You’re supposed to be listening to what’s said and unsaid. You’re supposed to rely on your training; you’re supposed to be open to what’s unfolding right here, right now, that may contradict what you know. You’re supposed to be collaborating—you practice from a relational approach. You’re supposed to be the expert: that’s the reason she’s here, because you have the training to help her figure out what’s going on.

You teach people to sit with uncertainty, to manage the anxiety that comes because we can’t tell the future. The biller’s calls remind you you’re supposed to know what’s coming and what to do next.

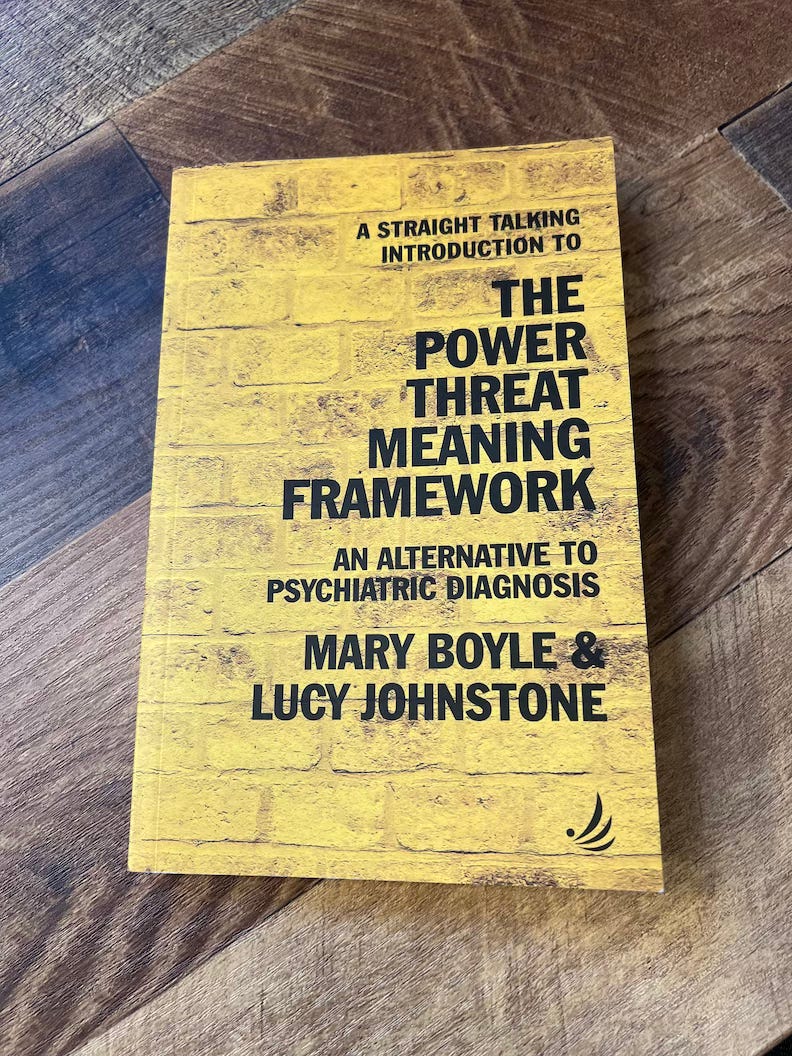

In 2020, the psychologists Lucy Johnstone and Mary Boyle published A Straight Talking Introduction to the Power Threat Meaning Framework.

The book distills the arguments of a longer paper, published in 2018, that critiques psychiatric diagnosis, arguing that our current diagnostic categories cannot be said to follow the same logic as medical diagnoses like diabetes and polio, even as the fields of psychology and psychiatry, especially, want mental health to be conceptualized and treated within the medical model.

Designed in collaboration with forty people, some of whom are therapists, others of whom are participants in the U.K.’s mental health system, the Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF) offers people the opportunity to create a narrative about what has happened to them and the responses they were taught and created in response to threats.

Whereas diagnoses are something you have, and can be static or enduring, perhaps for entire lifetime—a label that tells you who you are, or a prediction of how you will behave, or how functional you can expect to be—narratives are by design flexible and changeable. The narrative, because it is created by the person who is trying to better understand their suffering, centers their expertise, their story, and in doing so, reminds them of their own power.

The Framework can be used individually, but when it is used in a group, or with the help of a provider, it can more fully alter the person’s story. The framework begins by asking six questions, overlapping in their content, that are designed to place the person’s distress not in the context of mental illness, but rather of power.

What has happened to you? (How is power operating in your life?)

How did it affect you? (What kind of threats does this pose?)

What sense did you make of it? (What is the meaning of these situations and experiences to you?)

What did you have to do to survive? (What kinds of threat response are you using?)

What are your strengths? (What kind of access to power resources do you have?)

And to integrate the above: (What is your story?)

What these questions highlight is that distress occurs in a context. Rather than solely the product of a disordered brain or body, distress is a response to the operation of power: the relative power and agency (ability to act) that a person has at a particular moment in time, and their relationship to larger power structures, such as their economic position; their identities; their access to resources.

In the above fictional case study, the client’s circumstances are shifting rapidly. Already facing a number of life stressors, she finds herself suddenly in unexpected economic circumstances. Her white partner’s sense of masculine competence, thwarted by his job loss, puts him in increasing dissonance with dominant cultural representations of masculinity and success. Her competence in the household, in contrast to his “uselessness” in the home—if their relationship has been organized around binary gendered spheres of labor—could be a reason he’s become critical of her competence. Though he appears controlling and she’s starting to avoid him, he may be awkwardly trying to rebalance the power between them, afraid he’s going to loose her next. Or, he may be compensating for a sense of powerlessness by engaging in potentially abusive behavior that he may or may not have engaged in prior relationships: it’s too soon for the therapist or the client to know.

When the client, already trying to keep her head above water, is frightened by her desires to cut, and ashamed of her recklessness in spending money, and chooses the brave path of telling the therapist what’s happening, how can she be met in a way that enhances her sense of agency and power? If she is told that her behavior indicates the presence of a diagnosis, she could feel hopeless and ashamed. She could alternatively feel vindicated by its explanatory power, relieved there’s a “something” that can now be identified and addressed with a set of practices that are vetted by experts and have helped others.

One thing that occurred to me as I read the PTMF is that “diagnosis” is also a narrative, one that has a particularly compelling relationship to time. When I read the six questions of the PTMF, I can see how the answers would help a person’s story become three dimensional. In Western individualism, which is the foundation of many therapeutic approaches to distress, the person’s story usually begins in the past and travels along a linear track. Let’s make one up now:

“I grew up in a home that was chaotic and unstable; my parent’s marriage ended when I was nine; I have struggled to maintain close relationships because I don’t trust they will last; I act out and make up reasons to leave, even when a relationship is good, so I can stay safe; I am now lonely and frustrated and drinking too much; I don’t know how to interrupt this pattern and believe things can change.”

The PTMF would take this narrative and look “up” at the structures that framed this story of individual and familial dysfunction. It would look “out” at culture, and how the person learned to tell their story in this particular way, and how they learned that they weren’t measuring up, in terms of what their relationships “should” look like, and what a healthy and successful person “does.”

Diagnosis, in contrast, looks forward. It has a predictive quality to it; its utility is in part based on the idea that it can tell the “patient” what they can expect, either if they continue in the way they are now, or if they engage in “treatment.” The therapist or practitioner is expected to know: not only what’s wrong, now, but also what we can expect. It’s the therapist who, in giving the diagnosis, is put in the position of evaluating the present against an anticipated future.

Our therapist in our fictional case study wants to stay with the client’s experience; the therapist is very unsure of what’s actually happening and “how bad” things are. But the biller’s request for a diagnosis code keeps the therapist focusing on how what’s happening now will evolve. The more the diagnostic logic runs the show, the “sicker” the client appears to be getting, in medicalized terms, as the therapy progresses.

But if the therapist resists diagnosis and says the client is just adjusting to job loss and having a second child, and it’s revealed that instead the client’s impulsive shopping expedition was the first step on a ladder to mania and the therapist missed it and one day the therapist gets a voicemail saying the client was found raving in the parking lot with her kids in tow, not having anticipated the signs of her impending bipolar disorder . . . what then? The pressure on both the therapist and the client, inside this paradigm, is immense.

When we ask: what is the purpose of diagnosis? there is not one simple answer. One significant component of the debates that characterized the planning for the DSM 5 was the question of whether diagnoses are static and separable from one another, or whether they occur on a continuum. Even within the medical model, that is, there is debate about what a diagnosis is, and how it operates.

It is not that the PTMF is focused on diagnosis as the enemy to be defeated and replaced. Rather, it is asking: what is left out when we stay inside the logic of the medical model? What happens when story, which is how we know ourselves, the world, and our relationship to history, becomes as important as science, in helping us think through the best way forward? (As if science is not itself a story, but I digress . . .)

If you get a chance, write your answers to those six questions, and see what emerges. I’d love to know how it went.

Stay safe out there this week —

xo

Rebecca